Early in the century, the Nathanael Institute moved into the building that is now St Stephen’s Community House, and remained in that location until 1962. The institute was an Anglican Mission, with the major goal of converting Kensington’s Jewish population.[i] Despite this mission of conversion, that Nathanael Institute became more of a community centre for the market’s youth; in the 1930s, girls could learn to sew and cook there without the explicit pressure to convert from Judaism.[ii] The Institute became one of the most auspicious centres of Hebrew Christian life in the country until the 1960’s, due not only to the skills one could learn there, but the volunteer doctors with whom one could make appointments.[iii]

In the decades leading up to the 1930s, Toronto’s demographics had changed dramatically. In 1901, over 90% of Toronto’s citizenry could trace its heritage back to the United Kingdom. Explosive economic growth paired with more a more open immigration policy from 1901-1931 resulted in an influx of over 100 000 non-British people, the largest portion of this group being the Jewish community.[iv] The arrival of the Nathanael Institute signals the discomfort of the mainly Anglican population of Toronto in response to a growing Jewish population, as the Institute’s stated goal in establishing roots in the market was to ‘work among the Jews.’[v]

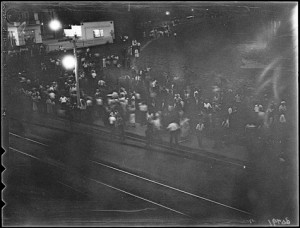

These tensions came to a head in 1933 when a riot broke out at Christie Pits Park, northwest of the market, between a Jewish baseball team and a Christian team who brought a blanket emblazoned with a swastika to their playoff game.[vi] Toronto was not always the diverse and accepting city it is considered to be today; Kensington’s diversity meant that it was shunned by most Torontonians in the early 20th century.[vii] For minority groups who were just beginning to move into Canada from around the world, the neighborhood surrounding the market provided a space where it didn’t matter that one was not from ‘around here’, or yet fluent in English. Sam Lunansky remembers the shtetl – Yiddish for ‘village’ – atmosphere of the community; ‘Everybody seemed to be a part of it, it doesn’t matter what nationality, everybody was at ease here… If you came here, it didn’t matter what you spoke.”[viii]

[i]Myrvold, Walking Tour, 19.

[ii] Cochrane, Kensington, 59.

[iii] Daniel Nessim,“The History of Jewish Missions in Canada” (paper presented to the Lausanne Consultation on Jewish Evangelism, Toronto, Ontario, April 27, 2004.) Accessed at http://www.lcje.net/papers/2004/nessim.doc on February 10th, 2013.

[iv] Daniel Hiebert, “Jewish Immigrants and the Garment Industry of Toronto, 1901-1931: A Study of Ethnic and Class Relations.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 83:2 (1993): 249.

[v] Myrvold, Walking Tour, 19.

[vi]“Christie Pits Riot of 1933.” Accessed February 9, 2013, http://www.christiepits.ca/history/riot.asp

[vii]Cochrane, Kensington, 35.

[viii] Ibid, 35.